LÓRÁND HEGYI - THE POSSIBILITIES OF METHAPHORICAL FORMS

Tamás Soós' work is characterized by perpetual changes, as well as by a peculiar coexistence and simultaneity of different forms of expression. His interest ranges from reflective gesture painting to meditative (monochromic) works, completely stripped of all meaning yet producing fully charged and highly personal spaces; from the imaginative stylistic metaphors of “quasi-Baroque” and Mannerist influence, abounding in art historical references and stylistic paraphrases, to the “Baroque Melancholies” which start out from the basic situation of a world without myths, and which is free of all pathos while being frivolously and impersonally decorative. He seemingly has no difficulty in passing from one artistic period to the next and from one system of forms to another, moving between his own stylistic metaphors ingeniously and with an apparent ease. For every new period he comes up with a new answer to the stylistic problems; for every new method he offers an "option” to create a new metaphor which is both valid, personal and reflective. Soós refuses to accept any taboos or proscriptions (in this respect his art is in line with the Postmodern concepts); he goes even further by refusing to accept any unappealable judgements, rules or obligatory sets of values. Nor does he accept precisely outlined and strictly defined areas for research, either, since research as an analytical approach to the possible forms of art is itself irrelevant to him. Rather than on researching or on surveying one particular area, Soós' work is based precisely on the method of free passage between the various fields. He regards art as a kind of open pasture in the history of culture and styles, to be roamed freely by artists in true nomadic fashion; his encampments, his temporary settlements in open territories, demonstrate the relativeness of boundaries, the non-evolutionary complexity of cultural-historical developments and the conditionality of the different systems of values, Soós "uses" the various stylistic metaphors, not in a formal sense but in the sense of appropriating the systems of values and the philosophical structures inherent in them. The unusual and provocative inconstancy of his art (which people often find confusing), the variability of his works, both in form and in vocabulary, are not due to a capricious streak in Soós' personality; rather, it originates in the demand felt by the artist to always address problems that are actual and current. He always tries to respond to the given intellectual situation, and in doing so he does not hesitate to use, as analogies or as cultural connotations not readily verbalized, the different layers of meaning hidden behind the visual topos. He presents us with visual objects, which, in their capacity as visual facts and by virtue of their own formal and semantic structures, make us aware of a particular situation. Instead of looking for universal analogies, his art is better approached from the direction of the individual object's power to increase our sensibilities and perceptiveness. In the I970s Tamás Soós was interested in pseudo-structuralist problems. Nevertheless, his painting already contained some uncontrolled and improvisative elements back then, which eventually came to open a new phase in his art. He started out from a systematically conceived and examined calligraphic painting, but soon turned his back on the analytical forms of art and made attempts to express his subjective Self-image in terms of stylistic metaphors. He created pure gesture paintings, in which the graphical qualities were gaining in importance. Immediately after developing the improvisative and informal method of painting, he introduced a number of new compositional elements and symbolic forms of cultural historical origin.

In his series entitled "Mythology” the antique motif, “The Judgement of Paris” is combined with the Christian motif, "St. John the Baptist", in such a way that both interpretations are projected onto the artist himself and the meanings describing the sensation of spontaneous and fleeting psychological state associated with the calligraphic transformation of the surface are "actualized", at the same time investing the motifs with personal and individual qualities. Soós also discovered the "Hannibal story” which served to him as a metaphor of certain attitudes as well as of answers given to various moral and historical problems, and which he used in a number of his oil paintings and watercolours.

In this period, Soós's oeuvre was based on the picturesque and imaginary world of a culture which, in that particular form, had never existed, and which came complete with its own heroic figures, ideas, dynamic art and colourful and chimerical architecture. A fine and complex colourism entered his painting, along with a kind of mannerist decadence: hedonism and ornamentalism to screen off the deeper feelings and dramatic gestures. While his ornamentalism was increasing in his small scale drawings and paintings, through its multiple meaning, symbolic references and art historical motifs, his emotionally charged thematic world came to express an artistic totality based on the impersonation of the "cultural metaphor”. This artistic programme enabled him to demonstrate the authenticity of his search for a new identity.

This is the viewpoint from which Tamás Soós' art should best be evaluated. His works have come to be regarded as the aesthetic forms of the free discovery of the artistic Self, the subjective pictures of his search for totality. And the only works that can inspire us with such notions are those which are authentic, powerful and have internal order.

With its neo-Baroque Naturalism and strange painterly qualities, "Caravaggio" meant a turning point in Soós' art. Painted in 1985, this particular work was the first of the artist's subsequent series of stylistic metaphors combining 'quasi-Baroque" elements with art historical references. It was in a round-about way, through the theatrical effects of deliberately amassed "artificial" elements, that his series of paintings re-interpreting the topos of "Heroic Landscape" reached the truly deep feelings: the realization of the common source of life and art, of destiny and free will. The dramatic pathos, loftiness and theatricality of Baroque style, which played such a prominent role in the history of art in Central Europe, was incorporated in Soos' visual world in such a way that it brought with it the sentimentality and radicalism associated with the "stormy past", while the passionate strive for majesticity was ironically reduced immediately, making everything relative: the subjects of individual evaluation and choice.

Painted in dark tones and radiating sombre splendour, "Mystic Landscapes" represent a cosmic world scenario controlled by mighty forces. In the otherworldly twilight, the vista of a bottomless abyss illuminated by small will-o-the-wisps scintillating here and there is opened for us. Underneath the stormy sky, a desolate and frighteningly barren landscape unfolds: the scene of the battle between mythical forces. Yet, this world scenario is built as a structured and enclosed, intended reality - this is emphasized by the half-drawn curtain between the imaginary space and our real world, the visual metaphor of the boundary of the "other world".

The curtain motif is gone from the series "Photo Drawing", along with the aesthetic "other world" based on precise relations and the system of symbols referring to the earlier expressions of artistic reality. Here the various aspects of representation themselves become the subjects of depiction. There is nothing really here that one could relate to; there are no objects and bodies to fill out the "empty" space: "emptiness" itself is filled with light, and the life of light. Light creates space around itself. As it approaches the photosensitive paper, light itself acquires a body: a body which moves through space and defines spatial relations. It is light that turns the black emptiness into a coherent and conceivable world, which we can metaphysically relate to. Darkness is "nothing": the void, the negativeness without life and intelligence, which is unable, even in its negative capacity, to exist without its antithesis, light. Darkness without light becomes the metaphor of "nothingness", while light is life itself.

In the almost monochrome paintings of the series "Metaphysical Landscapes", the surface is hardly moved at all by the tones of dark grey, lilac and black. Similarly to the case when one is groping around in darkness, mentally trying to reconstruct the surrounding space using bits of information gained through touching, in viewing these pictures we piece together the small portion of space directly around us from tiny details. Our experiences are based on the probing of sensible forms. The human eye is inundated with bits of visual sensations. Every visual sensation conjures a whole list of emotional associations. The great variety and indeterminable complexity of details combine into a fantastic world in our imagination in which cosmic forces clash while human destiny lies forever in the shadow of these great storms, being but a helpless toy dancing on the top of the restless waves. In this world, man is on a perennial journey of discovery, and in guiding himself he has nothing to rely on expect this tiny flames flaring up here and there. At the same time, this landscape is filled not only with loftiness and pathos, but also with a tranquillity of the soul.

Now that the furious storms are perhaps over, the mythical sky above the land in Tamas Soós' paintings radiates calmness and serenity, too. The small flames can provide some directions, with their perennial burning setting the precarious balance between constancy and change. These paintings represent states of mind in form of simple and obvious facts. The emotional gestures of personal manifestation are dissolved in the materialistic tranquillity of timeless and mythical conditions of the mind.

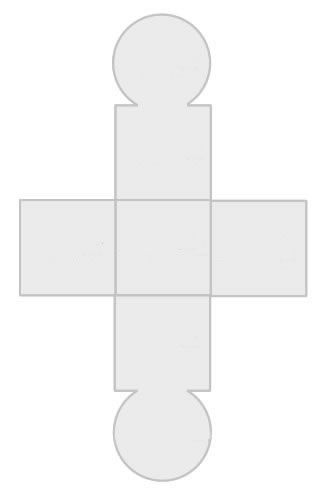

In the late 1980, parallel with the metaphysical landscape, new symbolic forms appeared in Soós' painting. He refers to them as "Melancholies". His motifs are simple yet ambivalent: ornamental motifs which nevertheless contain a hidden message of an ancient cult, the possibility of a barbarian and archetypical system of values. According to one possible interpretation, the black forms against the homogeneous red background represent female and male bodies. At he same time, their repetitiveness and linear arrangement reduce them to patterns. However, the artist's deliberate attempt to keep a distance from both monumentality and pathos seems to invest his work with the possibility of some ancient force, ambiguity and magic. The question as to what it is that we actually see is always left open; in a way "emptiness" forms the subject-matter.

Nevertheless, this emptiness is invested with new meanings om the course of the artistic execution. Sometimes the motifs, repeated over and over again, lend depth, body and mass to the forms, and also depth of field to the homogeneous basis, while at other times they do just the opposite: they flatten and banalize the motifs, confining them to the plane. Banality and the magic of an unknown myth are mixing in these pictures.

And it is precisely this shift in meaning that preoccupies Tamás Soós: what is that minimum which is required to render the images personal and ambivalent, magical and full of life.

For Tamás Soós, the act of painting clarifies problems and states positions; he is exploring the possibilities which lie in painting, while creating his own set of motifs and treasure-house of styles, which help him to express his new and complex Self-images incorporating momentary existence itself.

In:Tamás Soós – Baroque Melancholy, Ludwig Museum Budapest, 1995, catalogue