KRISZTINA PASSUTH - FROM MELANCHOLY TO MONOCHROME

In 1985, Tamás Soós organised his first solo exhibition in the Liget Gallery, Budapest. From that point on his art has witnessed the development of an individual painterly vocabulary, alongside the manifestation of an autonomous artistic personality. In comparison with the well-known contemporary Hungarian artists, his career of these fifteen years or so may appear relatively short, yet it has been all the more eventful.

Tamás Soós commenced his artistic activities at a time when the influences of the past era, with its constraints and shackles imposed from within and from the outside were not so much apparent, and the unfolding of a new style was neither controlled, nor hindered by the system's authorities. Tamás Soós belongs to the lucky young talents who were able to commence painting in an atmosphere of intellectual freedom, or more precisely, who were lucky to create the larger part of their oeuvre in this atmosphere.

A characteristic feature of freedom is that it comprises no angst, no self-censorship, no lies, no pressure; artists may choose freely from among the possible attitudes towards life - and from among possible stylistic tendencies. As Lóránd Hegyi analysed the period at hand, it was exactly in 1985 that New Subjectivity and Radical Eclecticism, and the outlook these trends manifested, had already permeated the thinking of artists. "At the same time, this means that the new art no longer requires those programs and arts systems that would serve a certain ideological - attitudinal clarification.”(1) Consequently, the new painting in Hungary witnessed a sense of 'classicisation as was apparent in the canvases of the more established artists, as well as of the younger ones - Lászlo Mulasics, József Bullás, Károly Kelemen, and Tamás Soós.

The choice of this outlook was quite conscious on Tamás Soós' part, since during the given period of time, this attitude connected the most intensively to the international trends, to the latest international achievements. From a re-interpretation of the calligraphic way of painting, Tamás Soós has arrived at the re-creation of classic tradition, and to the depiction of a peculiar form of figure.

Although Soós has not become a representational painter in the true sense of the word, and although individual motifs only have a role of allusion in his paintings, his artwork has born apparent marks of the original, traditional interpretation of painting. The essence of the traditional process is that the artist applies the paint with a brush onto the panel or the canvas choosing himself the required shades of colour, from the rich colour scale of the palette. The different paints mingle already on the palette, and finally on the canvas, in a singular and unrepeatable manner. The method of oil painting as was utilised during the Renaissance has been simplified by the centuries passed; the utilisation of acrylic has made the work quicker and easier but has left the whole process essentially unchanged. Even though the artwork has existed in concept before it is physically realised, the final form is born on the canvas, in the moment of painting, depending on the way the artist can give form to his/her original idea at the given moment.

The conscious acceptance of the painterly tradition, perhaps due to the very fact that this tradition comprises an order created by so many masterworks built upon one another, implies a greater challenge than the application of new genres and new media - which is also characteristic of our era.

Throughout Europe, the generation of the eighties returned to the "oil-canvas-brush" technique, whereas sixty years before, in 1920, the great avant-guard generation had stated - and moreover, proclaimed - the death of easel painting and of picture in general, that is, the end of painting. Despite the fact that there have been artworks created in the most diverse techniques ever since, a long time had to pass until the younger generation once again focussed attention on this "traditional" method with a conscious engagement, and even declared it as the most valid method relating to their time.

This younger generation was much too aware of all that had been created during the preceding decades, and even in the art of the previous centuries. By returning to the technique of the old "easel painting," members of this generation also attempted to internalise the intellectual, cultural content that related to this method.

The young painters gradually distanced themselves from their present time, and turned to the culture of the past to search there for points of reference, subjects, metaphors and signals which are able to convey something valid today, at the end of the 20th century, when taken out of their original environment and original background. They searched through different layers of the past, left behind the 20th and even the 19th century, and they found the epochs for themselves to which they could relate and in which they could find their own ways: Baroque, Mannerism, then skipping several centuries, Antique art.

Soós, right at the start of his career, consciously took this traditional pictoriality upon himself, did not experiment with new media, and did not attempt to employ different technical solutions. He constructed possible stations of his own development logically. He took calligraphy as his starting point - a tradition that may hardly be connected to a definite epoch, and which linked writing and painting, unfolding within the oriental cultures to be acquired later in a way by European culture, "Tamás Soós was engaged in calligraphic painting in the early eighties. His works of that period organised elementary signs of spontaneous improvisation into structures that depicted peculiar spatial problems..", Lóránd Hegyi writes.(2)

Calligraphy, even if in a latent way, has remained a vital element of Soós' paintings: the fragmented handwriting appearing in the pictures connects and organises the sometimes remote motifs. During the mid eighties, however, in a Post-modern spirit, he more and more often chose elements of antique mythology ("Hannibal's Column", "The Last Nymph", "Ionic Idea", "Hannibal") from which to create his own pictorial system. The large-scale arrangement, the sometimes bright red or pink tints, the emphasised angular brushstrokes add a contemporary colour scheme to the ancient subjects; the roughly sketched, angular strokes of the brush occasionally unite to form a curtain to partly cover the figure ("Mythology"). Concurrently with Mythology, Soós painted "Caravaggio", in the case of which he adhered to the original of the pictorial quotation more closely than he had done in the case of his subjects from antiquity where the motifs had been treated much more liberally. His "Caravaggio" was painted in 1985, after Caravaggio's painting, "San Giovanni Battista". The original painting belongs to Caravaggio's early masterpieces, preserved in the collection of the Capitolium Museum, presumably dating from the late 1500s. Its title was unclear for a long time, since despite the displayed attributes, it did not conform to the Christian outlook about Saint John the Baptist. The Italian master re-created the figure of Saint John in the Arcadian - mythological sense: he furnished the sacred subject with profane connotation. Tamás Soós enlarged the original painting (132x97cm) the double of its size (270x21Ocm), and he further transformed the already re-interpreted scene. The emphasised sculpturality of the original painting, as well as the erotic representation of the body modelled by lights and shades, became much more hazy. Instead of plasticity there is the decoratively colourful structure of patches, and instead of still-life elements modelled sculpturally there are the scratchy surfaces assuming dominance. After all, Caravaggio's "antiqued" Saint John perfectly fits into the postmodern, emphatically pictorial environment Soós created for him. When compared to other "re-interpretations" from the same time, such as, e.g., Tibor Csernus' "Saul I-II" and "Untitled", etc., one might sense a conspicuous difference. Csernus apparently re-composed works of the cinquecento-seicento in a way that at first sight they astonishingly resemble the originals, or rather, they seem to be direct versions of them. As opposed to Csernus' method, the resemblance in Soós' work is mostly limited to the setting; both the elaboration of the details and the atmosphere of the whole are of the present day, and evidently his intention is far from striving to evoke the atmosphere of the past epoch one and the same. His “Caravaggio" painting, despite all the similarities, is much more a re-interpretation than a mere copy.

In his subsequent period he depicts dim, dissolved surfaces on large sized canvases, where the angular brushstrokes alternate with extremely soft, interfusing colour patches ("Baroque", “Fire", "Landscape", "Metaphysical Landscape", etc.), evoking, above all, Turner's method of painting or that of Monet in his late period.

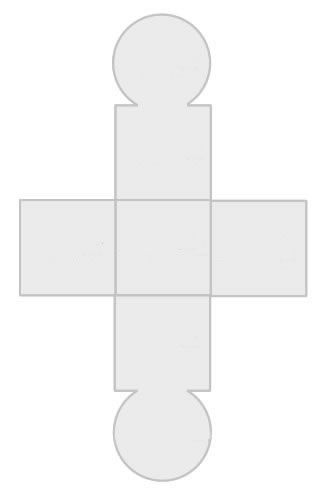

From 1991, Soós' art has witnessed the appearance of a radically new approach in that on the monochrome canvases he shapes figures majestically reduced to the point of schematism. The blue or black puppet-like motifs, standing out against the bright red background, make the first impression on the onlooker via their silhouette-like appearance, as did Henri Matisse's cut out figures. Soós sets the red and black colours in sharp contrast [in certain cases the background is black and the motifs are black, or the background is white while the figures are black). The characteristic tri-colour - black-white-red - of the Russian avant-guard here assumes a totally different meaning than in the 1910s and 1920s. The colour trinity emphasises the opposition of the surface and the motifs, the play of the positive and the negative becoming of primary importance. The positive-negative effect includes the independence of certain impressively large sized black silhouettes leave behind the confines of the canvas and start an independent life of their own in the form of statues of black papier-mache. They gain existence and sense, however, only in unity with and as a function of the composition: they project, as it were, into sculptural forms that which exists on the canvas merely in two dimensions. By this, the painter no longer intends to produce the illusion of three dimensions - he does not need to do so - as instead of generating the appearance of spatiality, the protagonists of the composition exist in real space, in authentic three-dimensionality. The series is entitled "Baroque Melancholy", which unambiguously refers to a post-modern inspiration. Tamás Soós' recent paintings have been born under the aegis of development and change from the complicated to the simple, from the colourful to white, from the decorative to the fully considered and mature. Following the emphatic contrasts of colours and forms, there is an infinite scheme of tints within the monochrome compositions demonstrating white on white: the motifs, hardly discernible on the canvas, level with the background.

The first representatives of monochrome painting - the Russian Kazimir Malevich and the Polish Wladislaw Streminski - in the 1910s and the 1950s, respectively, saturated their white on white, perfectly objectless compositions with a plethora of intellectual content. This tradition has latently survived ever since, emerging from time to time to provide new, metaphysical dimensions for artworks by contemporary artists. Tamás Soós perceptibly follows their path, with his paintings becoming gradually simpler, demanding increasing attention and yielding themselves for revelation less and less easily.

1 Hegyi Lóránd, Alexandria, Pécs, Jelenkor, 1995,149-150.o.

2, Hegyi Lóránd Alexandria, in., 1995, 233

in: Tamás Soós – Melancholy 1980-2001, Catalogue